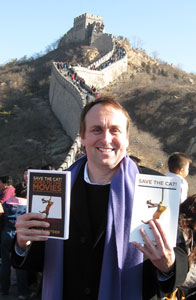

Blake Snyder’s book Save the Cat! gets a little more detailed than most manuals about what should happen minute-for-minute in a compelling film. Today we’re going to look at the first three BEATS, or mini-acts, he has identified within all good screenplays. These beats are described in Blake Snyder’s BEAT SHEET, and are laid out in the last post. I’m using the sheet myself to help keep me on track with the screenplay I’m currently writing. While it doesn’t write the script for you, it does make you feel less alone during what is an otherwise solitary process.

I’m going to be applying this system to two films that could not be further apart in style and tone (though both, coincidently, deal with the same theme — the death of a child). ORDINARY PEOPLE (screenplay by Alvin Sargent, based on the Novel by Judith Guest), and MINORITY REPORT (screenplay by Scott Frank and Jon Cohen, based on the short story by Philip K. Dick), seem worlds apart, but lets see if they both adhere to the Blake Snyder Beat Sheet. Maybe we’ll stump Save the Cat! Maybe we’ll find that it’s right on the nose. Maybe somewhere in-between…

His first Beat Snyder calls the OPENING IMAGE, and happens on page 1. Here’s what he has to say about it:

“The very first impression of what a movie is — its tone, its mood, the type and scope of the film — are all found in the opening image….” — Blake Snyder

ORDINARY PEOPLE: The opening image of the film is an establishing shot of a lake. It appears completely serene. The camera pulls back and we move through peaceful vignettes of autumn trees and the manicured lawns of upper-class neighborhoods.

So far, so good. That lake that fills the first frame of the movie is where, we find out later, the inciting incident of the film took place — it’s where Conrad’s brother drowned, leaving his family in the broken state we find them in at the start of the film. But for now, much like Conrad’s family, it has the appearance of serenity. At page one of this script, we cannot imagine the raging storm simmering beneath each of the family member’s icey veneers, or the lake’s ability to kill. Score one for the Beat Sheet!

MINORITY REPORT: The film opens with a barrage of blurred and warped images depicting a murder. The theme of “Eyes” is prominent — there are multiple shots of eye balls and glasses and a child’s paper mask of Abraham Lincoln having its eye holes cut out.

The film certainly gets to the point — the movie’s going to be about murders and seeing; can one believe what they are seeing? — so BAM! Start with a murder and shots of eyes. Spielberg may not always be subtle, but he is effective. It also foreshadows a creepy scene later in which Tom Cruise has his eyes removed. Another score for the Beat Sheet.

The second beat is called THEME STATED and occurs around page 5.

“…someone (usually not the main character) will pose a question or make a statement (usually to the main character) that is the theme of the movie. “Be careful what you wish for,” this person will say or “Pride goeth before a fall” or “Family is more important than money.” It won’t be this obvious, it will be conversational, an offhand remark that the main character doesn’t quite get at the moment — but which will have far-reaching and meaningful impact later. This statement is the movie’s thematic premise.” — Blake Snyder

ORDINARY PEOPLE: Dr. Berger tells Conrad, “I’ll be straight with you, okay? I’m not big on control.” (page 19)

Well, while I agree with Snyder that the Theme Stated moment works well in most films, I’m willing to let this subtle film off the hook a bit. The portrayal of Conrad is just too naturalistic for this moment to be played out the way it would be in the average Hollywood film.The closest moment I can find to the Theme Stated beat Snyder intends comes at minute 19. Conrad has his first visit with his therapist, Dr. Berger. When asked what he hopes to accomplish with therapy, Conrad says he wants to have more control over himself so everyone can stop worrying about him (he had attempted suicide after his brother died in front of him during a boating accident). Berger responds with “I’ll be straight with you, okay? I’m not big on control.”

This sums-up the message of the film. It’s only when Conrad and his father, Cal, start to open up, cast aside their facades of normality and lose control of their emotions that they can really start to deal with the tragedy they’ve suffered. Whereas Beth, Conrad’s cold mother, will insist on continuing to play the part of the woman in control — and it will lead to her estrangement from her family.

A little off their Snyder Beat Sheet. I like the Theme Stated idea. But I’m not sure page 5 is where is needs to be.

MINORITY REPORT: “Careful, chief. You dig up the past, all you get is dirty.”

After one of the pre-cogs shows John an old murder for unknown reasons, he begins investigating its origins. The gate keeper of the old murder records tells him the quote above. This comes at minute 33, and is a central theme of the movie. The more he digs, the more disturbing details come out about his part in a crooked system. I don’t know, Blake. Maybe your page 5 estimate’s a little strict. It seems to me that both these movies wait until after the set-up to throw a little dogma at our hero. There’s an earlier contender, at minute 16, where John’s blind drug dealer tells him “In the land of the blind, the one-eyed-man is king.” But while this old saying can refer to many aspects of the film, it doesn’t serve to warn John of, or direct him towards, the challenges he will face later on in the story.

My own preference for the Theme Stated moment is to place it anywhere in Act I that it fits. As long as it shows-up before the downward spiral of Act II begins, the line will resonate.

The third beat is the SET-UP (it’s less a beat than a rounding-out of beats 1 and 2, along with some other plot points that should be included within pages 1-10).

“The set-up is the place where I make sure I’ve introduced or hinted at introducing every character in the A story. Watch any good movie and see. Within the first 10 minutes you meet or reference them all. “

“This is the place to stick the SIX THINGS THAT NEED FIXING. This is my phrase, six is an arbitrary number, that stands for the laundry list you must show — repeat SHOW — the audience of what is missing in the hero’s life. Like little time bombs, these SIX THINGS THAT NEED FIXING, these character tics and flaws, will be exploded later in the script, turned on their heads and cured. They will become running gags and call-backs. ” — Blake Snyder

ORDINARY PEOPLE: In the first ten minutes, every character in the A story is there for roll call, along with most of the B story characters. Conrad, his parents and Dr. Berger all have lines, along with Conrad’s friends and his future love interest, Jeannine.

That’s just like the Beat Sheet says.

And the SIX THINGS THAT NEED FIXING: Conrad wakes-up at night from nightmares. He’s aloof with his friends and family. Cal wants him to talk to a therapist but Conrad’s resistant. He’s not eating and looks like hell. Cal worries about his son constantly. He also seems to notice on some level that Beth is disengaged from her son. Beth is impatient with Conrad’s lethargy and just wants him to start acting normal again. Lastly, Conrad clearly has a crush on Jeannine but is shy around her.

That’s six things. And all of the main characters have been introduced. Another win for the Beat Sheet.

MINORITY REPORT: In the first ten minutes, we meet John, Agatha the pre-cog, Danny from the Justice dept., and John’s police buddies.

But we don’t meet Lamar, John’s mentor and, as it turns out, nemesis until min 21. Nor do we see his ex-wife until min 20. Both of these characters become very important to the story. But I’m starting to find, as I continue conducting this test, that Minority Report is a stretched out film. As we’ll discuss in the next post, it doesn’t even get to Act II until min 38.

SIX THINGS THAT NEED FIXIN’: John has not gotten over the kidnapping and presumed death of his son. As a result, he has lost his marriage and developed a bad addiction to what look like futuristic, asthma inhalers. He runs a special unit of the police called precrime that arrests people for murders they will, but have yet to, commit — which feels icky, karmically speaking. The Justice Department, feeling icky about it as well, has sent a representative to investigate the unit and possibly take away it away from John. His drug addiction may be used as evidence against him when the Justice Department makes their move.

All of the above problems happen in the first twenty minutes, not ten. As mentioned before, this is a slow moving movie — add ten minutes to almost every beat and it seems like you’ll be on track. But Speilberg deserves a pass after so much solid work — let’s not forget, he brought 1941 to the world, among other less known fare.

In the next post, we’ll apply the next three beats to our two test films and subject Blake Snyder to harsh scrutiny for rules he most likely meant for us to take with a grain of salt. Should be fun…

Also, check out my Screenplay Tip of the Day at my other blog: screenplaytips.wordpress.com